The Last Christmas Present

By Jack Cashill

Nana had the best collection of literary porn my 13-year-old eyes had ever seen: sultry classics like D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterly’s Lover ; steamy cult favorites like Henry Miller’s Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn; even sleazyy potboilers like Peyton Place and The Carpetbaggers. You name it, she had it, we read it.

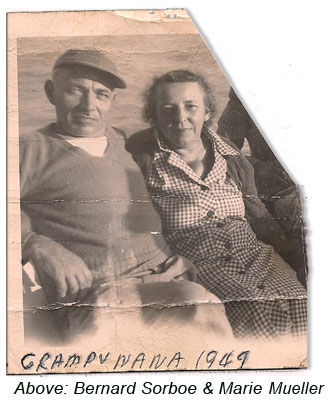

My father’s mother, Nana and her sister Lil had just moved in with us after Gramps died. Gramps had been the quintessential granddad--a kindly, weathered old gent who could carve faces on coconuts and actually put ships in bottles. Only at his death did I learn that he was something other than my natural grandfather. And only after living with Nana would I understand what happened to the real one, but more on that later.

My father’s mother, Nana and her sister Lil had just moved in with us after Gramps died. Gramps had been the quintessential granddad--a kindly, weathered old gent who could carve faces on coconuts and actually put ships in bottles. Only at his death did I learn that he was something other than my natural grandfather. And only after living with Nana would I understand what happened to the real one, but more on that later.

Nana's arrival put added pressure on our already burdened domestic ecology. Twisted like a corkscrew with arthritis and missing her left leg, Nana needed space and attention. To accomodate her, my parents had to give up their bedroom and camp out in the living room on a famed Castro Convertible, the silly pleasures of which--folding and unfolding, jumping up and down upon--eluded them entirely.

Worse, the neighborhood had begun to go. In fact, we were getting an advance peek at the new ‘60’s phenom--Welfare Americanus--that would drive away the established black families even more quickly than it would the white and rewrite urban history. Two doors down, when the Hanneberry’s moved out, three quasi-families moved in, 16 kids total. Across the street, a conglomerate almost identical in size, structure and decibel-count moved in soon after. Down the street, a family of “white trash” descended upon us with two “slut” daughters--make my day!--and their myriad gentleman callers of all races, creeds, and car makes. Stubbornly my father would smoke his Raleighs on the front stoop after work and seek the peace outside he could no longer find within. But times, they were a changing.

On Thursdays of each week, however, time stood still. On these charmed days Nana’s sister Caroline would take her and Aunt Lil out for a ride. We weren’t sure where. We didn’t really care. All that concerned my brother and me was that they went. As soon as their car pulled out, we would sneak into Nana’s room and speed through her erotica like a pair of Evelyn Woods in heat. Ah, the glorious Thursdays of my youth!

In the beginning, we liked to visit even when Nana was there. She would embrace us as best she could with her gnarled hands, and if she were too crippled to bake cookies, who cared? The books compensated quite nicely. During one early visit, however, Aunt Lil dropped a plate of Scooter Pies meant for us, and Nana--yo, grandma!--retaliated with a laser of invective vile enough to make Henry Miller cringe. Stung, Lil whimpered off to a neutral corner, wishing our Nana to the deepest reaches of that fiery region whence she presumably came. Nana, as we came to see through Lil's eyes, was the classic big sister from hell.

The revelation of Nana’s darker side scarcely phased my brother. Deprived of attention at an early age--he and I being ”Irish twins,” born less than a year apart--Bob saw Nana as something of a role model, a mentor in sibling oppression. Alone among us, he remained genuinely attentive to her needs. At Christmas, it was always he who would shake us down for change and buy Nana hand-lotion or some other gee-gaw in that neutered aisle of our five and dime dedicated to nuns and grandmas.

TWO YEARS AFTER Nana’s arrival, on “Little Christmas”--January 6, my father died. Like most fifteen-year-olds, I lived my life resolutely in the here-and-now, so much so that 25 years would pass before I realized that my dad and JFK (our other neighborhood hero) died the same year. At the time, what mattered most were the immediate aftershocks, none more sudden than my mother’s move to evict Lil and Nana.

My brother and I protested, he presumably out of affection, me clearly for the books. But my mother would not be swayed. “She's a nasty old lady,” she told us. “She’s got to go.” My brother argued that being crippled like that would make anyone nasty. Not so, answered my mom, Nana was born nasty. Then came the shocker. “She was so nasty she drove your grandfather away 35 years ago, and he hasn’t been heard from since.” End of discussion. Nana was history. And so, alas, was her library.

But life went on. My oldest brother got married and left home. Bob won a football scholarship to a college in Virginia. And I stayed behind with my little sister who eagerly awaited the return of our Grandpa from Gilligan’s Island or wherever it was that he had wandered.

In the streets, things got steadily weirder. “Midnight plumbers” deplumbed the house next door the very night our neighbors moved. Down the block, a man burst into an elderly neighbor's parlor, unplugged the TV while she was watching it, and waltzed off with it as if he had won it at bingo. For protection, an eccentric friend and neighbor took to keeping a full-size alligator in his bathtub and displaying him occasionally at the window. And in my own playground, once a sanctuary of bias-free mayhem--"no autopsy, no foul"-- I got a new nickname, “Whitey.” Thanks, fellas. It was times like these that I began to appreciate the value of a big brother, especially one who was about 230 pounds of unrefined elbow. I almost missed him.

In November, Bob came home for Thanksgiving. Never one to identify with our humble asphalt heritage, he had decided to transform himself into a southern gentleman. To accomplish this, he changed his middle name from Andrew to Andrews, no longer wore socks (huh?), and talked to us as if we were some lowly species of carpetbagger. Still, he remained devoted to Nana and cajoled us into visiting her, our first visit since her departure.

After his brief stay, "R. Andrews" headed back to Virginia. A few days later, Nana died unexpectedly. Not wanting R to drive all the way back, we decided to tell him after the funeral. And a spirited funeral it was. The reception apres, in fact, seemed more like a happy hour than a dirge.

A few weeks later, Bob came back for the holidays. Christmas morning, we gathered around the tree and distributed the presents that we had placed underneath. From deep in the pile, my sister plucked one out wrapped chaotically as was my brother’s wont. “From Bob,” she read casually, “To . . . Nana?"

Mother of mercy! We forgot to tell him. Sis gently clued him in, "She's dead, you idiot!"

It was true, we added, and we filled in the details. For a moment Bob said nothing. Neither did we. Then a great, silly, infectious laugh rose up from my sister that she tried to suppress but couldn't. Then I started. Then my mom. And finally even Bob. And for a long time we laughed like total fools. For despite the tragedies in our own lives, and the absurdities of the world around us, it was Christmas, this was America, we had each other, and who knows, Grandpa Cashill might still show up richer than Scrooge McDuck. And if that wasn't enough to feel good about, then what the hell was?