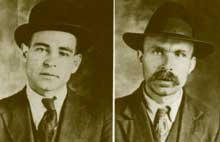

Nichola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti

Get your signed copy of Hoodwinked here

![]()

© Jack Cashill

Posted April 10, 2007 - www.frontpagemag.com

A new and much heralded documentary by Peter Miller, simply titled Sacco and Vanzetti, purports to tell the true story of these two doomed Italian immigrants.

Like so much produced by the left, however, the film tells us more about the filmmaker and his enthusiastic reviewers than it does about history

A review by Phil Hall in Film Threat captures Miller’s intent and the typical progressive critical response. According to Hall, this “excellent documentary” shows how a “hideous prejudice against Italian immigrants” and a “fear of European rooted political movements” led to the railroading of two innocent men—men who “actually abhorred violence.”

This is utter nonsense. In reality, the reporting on the trial stands as a brilliant prototype of the Soviet ability to manipulate the world media to its own ends. As Miller and his reviewers have unwittingly proved, contemporary leftists are as eager to be duped as their literary predecessors, but they have far fewer excuses for being so.

In the way of background, the early Soviets absorbed not only Karl Marx’s economics but also his morality, such as it was. In their pursuit of the larger truth—pravda—they scorned any petty factual truth—istina—that stood in its way. The man who brought this new system of power, the so-called “lying for the truth,” to the West was an unlikely German Communist named Willi Munzenberg. A sort of roughneck publisher, Munzenberg had an instinctive feel for the power of the media and persuaded Lenin to let him apply it.

Willi Münzenberg

As Stephen Koch details in his masterful book, Double Lives, Munzenberg pioneered two new lines of secret service work: the propaganda front controlled covertly from afar and the “fellow traveler,” a friend of the revolution who voiced the dogma du jour as artlessly as if it were his own. The messages being voiced varied wildly over time, but they remained consistent in their intent, namely that “any opinion that happened to serve the foreign policy of the Soviet Union was derived from the most essential elements of human decency.”

On May 5, 1920, police from several small Massachusetts towns set a trap for a man named Michael Boda, a suspect in an aborted Bridgewater payroll robbery five months prior. Stumbling into the trap were Nichola Sacco, a shoemaker, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, a fish peddler. They had taken a streetcar to Boda’s house to retrieve his car and were promptly apprehended.

Three weeks before their arrest, there had been a second payroll robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts—this one successful and lethal. When arrested, Sacco had in his pocket six obsolete bullets, which matched the bullet found in the body of Alessandro Berardelli, a security guard killed in the South Braintree robbery. Stuffed in Sacco’s waistband was the gun through which the fatal bullet had been fired. As to Vanzetti, he carried Berardelli’s revolver in his pocket as well as four shotgun shells of the sort used in the attempted Bridgewater robbery.

On September 14, 1920, Sacco and Vanzetti were both indicted for the South Braintree murder. At their request, the trial was delayed until May 1921. At first, Sacco and Vanzetti held little appeal for anyone. A socialist newsman sent up to review the case quickly lost interest. “There’s no story in it,” he reported back to his editor, “Just a couple of wops in a jam.”

A local Italian anarchist cell did come to the pair’s aid before the murder trial and formed a Defense Committee. The committee enlisted the help of the fledgling ACLU among other sponsors and the aid of maverick western attorney Fred Moore. An eccentric leftist in the Clarence Darrow tradition and a cocaine addict, Moore quickly came to the opinion that there was no hope for the pair unless he could politicize the trial.

Fred H. Moore

As Moore projected the case, Sacco and Vanzetti were no longer just a pair of thugs on trial for murder. They were powerless immigrants persecuted for their unpopular political belief and ethnic origins.

In fact, the two Italian immigrants had met when they both fled to Mexico in 1917 to avoid the draft. Upon their return, disillusioned with their adopted country, they got involved in the then popular anarchist movement. This movement occasionally turned deadly. An anarchist had assassinated President McKinley twenty years prior. On September 16,1920, two days after Sacco and Vanzetti were indicted for murder, Italian anarchists blew up the Morgan Bank in lower Manhattan, killing thirty and injuring three hundred more. This Wall Street institution was as iconic in its day as the World Trade Center was in ours, and the iconoclasts were just as deadly and determined.

Despite the risks, there was a method to attorney Fred Moore’s madness. The pair had to come up with some rationale as to why they had been looking for Boda’s car, why they were nervous around the police, and why they lied to the prosecutor.

Their unpopular political beliefs made as good an excuse as any. Upon advice of counsel, and against the advice of the judge, they told the jury about their radicalism and their draft dodging. They spun the story that they were seeking Boda’s car as a place to stash their anarchist literature. The jurors didn’t buy the story. They convicted the pair of murder.

With the verdict rendered and an appeal in process, Moore and his allies went to work on public opinion. If they were to paint Sacco and Vanzetti as innocent victims, they had to identify a guilty party, and for this role they settled upon the Massachusetts legal establishment, now the evil instrument of the pair’s “judicial murder.” Even before Munzenberg got involved, Moore pursued this strategy vigorously and without conscience. Before the century was out, his spiritual heirs would use the same strategy for a score or more celebrated radicals, Mumia Abu Jamal and Leonard Peltier among them.

In 1923, however, Sacco fired Moore. It seems that Moore lost confidence in the pair’s innocence, and Sacco, in the midst of a paranoid episode, lost confidence in Moore. With Moore gone, the case lost its luster. As it dragged through the appeals process, Sacco and Vanzetti morphed back into shoemaker and fish peddler, their Cinderella moment seemingly over.

In 1924, fate intervened when Lenin died and Stalin replaced him. Always the realist, Stalin had no illusions that the Comintern or the fledgling Communist Party in America could inspire an American revolution. He focused his American efforts instead, notes Koch, “on discrediting American politics and culture and assisting the growth of Soviet power elsewhere.”

With Stalin’s blessing, Munzenberg and his colleagues set out to find a case that would undermine the idea of America, which at the time held great sway throughout the world. America was widely perceived as the land of opportunity, the ever beckoning home of the free and the brave. “Give us your tired, your poor” indeed! For the Soviet experiment to prevail, the American experiment had to yield. The world had to see America through fresh, unblinking eyes, not as the great melting pot but as a simmering stew of xenophobic injustice.

In 1925, the Comintern came looking for Sacco and Vanzetti, glass slipper in hand. “It was Munzenberg’s idea,” his widow Babette Gross would casually tell Stephen Koch, not realizing the full implications of her remark. Working with the Comintern, Munzenberg had set up an organization in Chicago called the International Labor Defense and gave it, as a first assignment, the creation of a worldwide myth around the fate of Sacco and Vanzetti.

Almost immediately, “spontaneous” protests sprung up throughout the world. Europe’s great squares filled with sobbing, shouting protestors, declaiming the innocence of the immigrant martyrs and denouncing the vile injustice of their persecutors.

Only rarely did Munzenberg and the Comintern attempt to dictate literary response to a given event. When they did so, it was usually in Europe and often with writers whose sympathies they could count on. In America, they preferred to create theater and allow the actors to find their way to the parts.

The casting call for the Sacco and Vanzetti protests attracted a who’s who of literary leading lights. Prominent American authors Upton Sinclair, Katherine Ann Porter, John Dos Passos, and Edna St. Vincent Millay not only protested the seeming injustice but also created literary works around it. Scores more picketed, protested, or signed petitions. International luminaries joined in as well.

The modes of expression differed. Edna St. Vincent Millay, for instance, unleashed her outrage in a poem, “Justice Denied in Massachusetts.” Upton Sinclair, the author of The Jungle, expressed his in a two volume, 750-page novel called Boston.

Despite protestations to the contrary, progressives worldwide have historically shown little faith in the wisdom of their fellow citizens. Given this bias, each of the progressive authors who wrote about the Sacco and Vanzetti case began his or her work with the a priori assumption that the pair was innocent. They could do so in good conscience because, in their view, the jury that had reviewed the evidence and found Sacco and Vanzetti guilty was not to be taken seriously. As they saw it, these twelve ordinary Massachusetts citizens, like most ordinary Americans, were easily inflamed and incapable of reason. In reality, however, the jurors were neither.

“The only thing we considered in the jury room was whether the defendants were guilty as charged,” juror John Dever would recount some years later, a sentiment shared by every juror interviewed. “I can repeat it over and over again. That talk of radicalism is absurd. Radicalism had nothing whatsoever to do with it.”

As the August 1927 execution date approached, Munzenberg went to work. He had finessed famed liberal jurist Felix Frankfurter to write a defense of the pair, and he arranged for it to be distributed throughout the world. In London, H.G. Wells disseminated an inflammatory summary of Frankfurter’s writing that quickly became accepted British wisdom. Protest movements swelled in major American cities and European capitals. On the night before the execution, five thousand militants roamed the streets of Geneva savaging everything from cars to movies that smelled of America.

On the night of the execution, August 22, an outpouring of rage and grief swept the world and left common sense buried in its wake. The French Communist daily Humanité published an extra edition with one word on the front cover, Assassinés. Reacting to the news that the pair had, yes, been “assassinated,” crowds swarmed through the streets of Paris on the way to the American embassy, ripping out lampposts and smashing windows. Only the tanks that ringed the embassy stopped them. In London, masses of people surged around Buckingham Palace, shouting and singing “The Red Flag.” Germany meanwhile witnessed a series of demonstrations and torchlight parades more intense than any the volatile Weimar Republic had yet seen. A half-dozen German demonstrators were killed during the course of them.

Munzenberger had pulled all the right strings in this international puppet show. True, Sacco and Vanzetti were executed, but it had never been his job to save them. In her memoir, The Never-Ending Wrong, published on the fiftieth anniversary of the pair’s execution, Pulitzer Prize winning author Katherine Ann Porter relates how she first came to understand this. As the final hours ticked down, Porter had been standing vigil with others artists and writers in Boston. Ever the innocent liberal, Porter approached her group leader, a “fanatical little woman” and a dogmatic Communist, and expressed her hope that Sacco and Vanzetti could still be saved. The response of this female comrade is noteworthy largely for its candor:

“Saved,” she said, ringing a change on her favorite answer to political illiteracy, “who wants them saved? What earthly good would they do us alive?”

A letter from Upton Sinclair found by a southern California collector in 2005 sheds some new light on the literary influence on the case. As reported in the LA Times, the critical letter was from Sinclair to his attorney, John Beardsley.

The letter revealed that Sinclair had met with Fred Moore, the anarchists’ former attorney, in a Denver motel room. Moore "sent me into a panic," Sinclair wrote in the typed letter.

Upton Sinclair

“Alone in a hotel room with Fred, I begged him to tell me the full truth," Sinclair added. " … He then told me that the men were guilty, and he told me in every detail how he had framed a set of alibis for them."

As Sinclair made clear in this and other letters, he proceeded to write his book about the pair as though they were innocent. "My wife is absolutely certain that if I tell what I believe, I will be called a traitor to the movement and may not live to finish the book," Sinclair confided to a friend in 1927.

Not to worry, though. A slew of academics have since rushed in to discredit the letter. Although they have not challenged its authenticity, they charged conservative critics with taking the Sinclair quote out of context.

“I had heard that [ Moore] was using drugs,” Sinclair also writes in the same letter, much to the academics’ relief. “I knew that he had parted from the defense committee after the bitterest of quarrels.”

That explains everything. Sacco and Vanzetti were innocent after all. Now, back to Mumia and Leonard and Alger and Tookie and . . . .

Editor's note: For a more complete account of this phenomenon, read Jack Cashill's amazing book, "Hoodwinked: How Intellectual Hucksters Have Hijacked American Culture.